This is the third part in an on-going blog series about building an event sourcing system in Ruby using AWS Serverless technologies.

It was originally part of Aggregate Persistence. It grew a little bit too large for my tastes and I opted to separate this portion into it’s own article. Enjoy!

In event sourcing, events are stored in a database called an event store. We’ll design one using AWS Serverless technologies and it will be the backbone of future articles that extend the event store.

After the overview, we’ll implement the first component - the DynamoDB table.

What is an Event Store

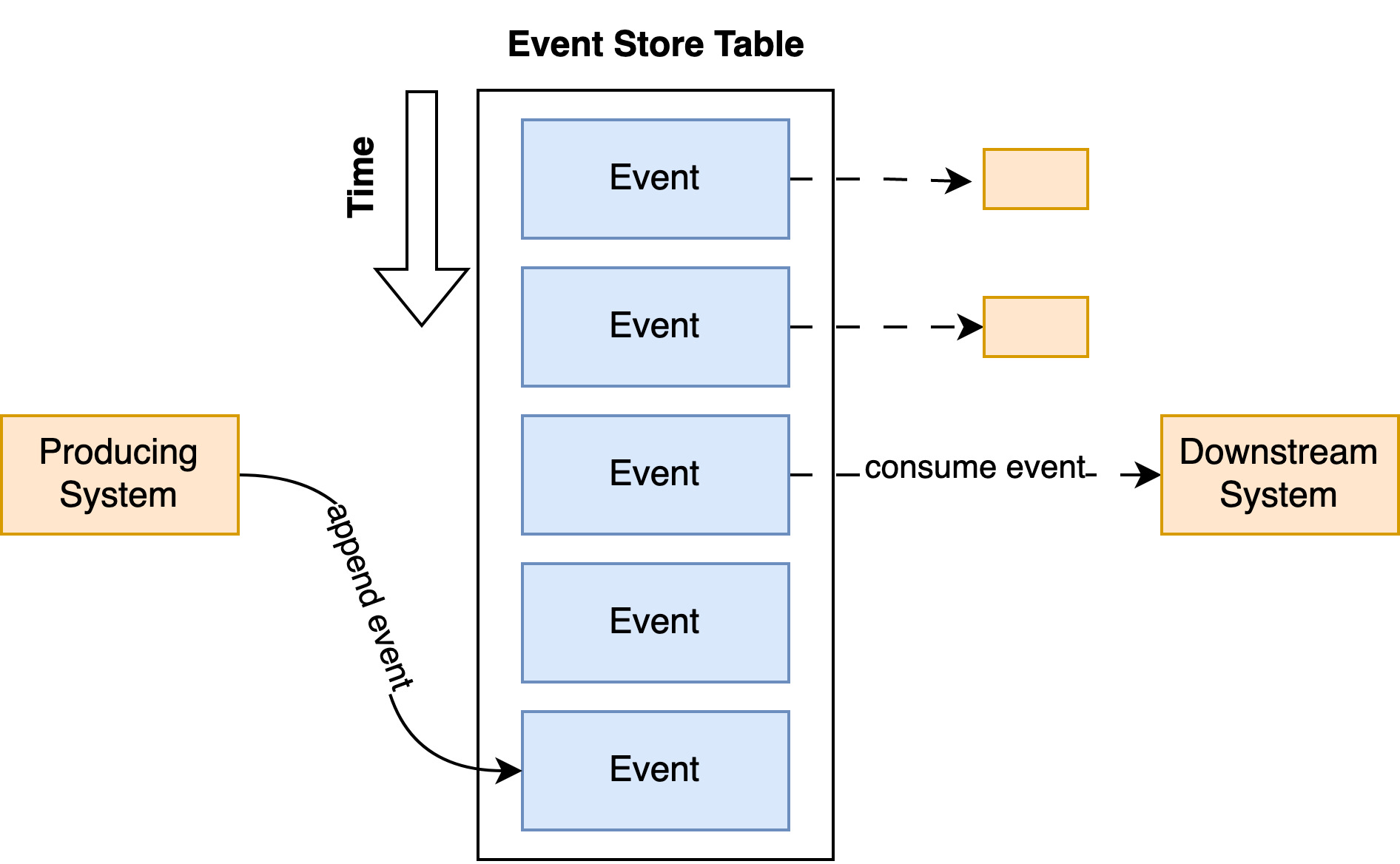

Event stores are databases for event sourcing systems. It’s often built on top of existing database technologies, such as PostgreSQL, to meet specific event sourcing criteria. It allows querying and persisting events and is the single source of truth for system data.

Events are stored in an append-only table. Meaning, events are immutable and inserted only at the end of the table.

When events are appended, they become available to the external world through polling or consumers reacting to them on streams. This is usually facilitated through a CDC feature of the database or by external technologies and make events available to downstream consumers.

As event sourcing has become more popular, databases specifically designed to be event stores have emerged.

For example, EventStoreDB, originally released by Greg Young, is an event store that packages persistence and streaming needs into a single technology. It’s tuned to meet event sourcing needs and cannot be used as a relational database or document storage.

Open source event stores built on top of existing technologies have emerged as well. MartenDB is a great example of this. It provides features to act as both an event store and document storage.

Designing an Event Store

While an event store may be implemented with many different technologies it should meet 4 key criteria:

- The ability to persist ordered events.

- The ability to fetch a range of events (or all events).

- The ability to push events to downstream listeners.

- The ability to prevent conflicting changes happening at the same time.

Our event store will be implemented using DynamoDB, Lambda, and Kinesis. Let’s review each criteria in turn.

The Ability to Persist Ordered Events

Event ordering is paramount for event sourced aggregates. Aggregate events out of order can have diasterous effects.

For example, in accounting systems, accounts that are overdrawn (have negative funds) are usually subject to fixed fees regardless of the time span they are overdrawn.

Let’s say Bob deposits 100 dollars on Monday and withdraws 50 dollars on Tuesday. This means there are two events stored in the event store:

- FundsWithdrawn: $100 on Monday

- FundsDeposited: $50 on Tuesday

If the downstream application responsible for applying overdrawn fees received the FundsWithdrawn event first before the FundsDeposited, poor Bob would loss money (and the customer support member receiving a not-so-fun phone call)!

The Ability to Fetch a Range of Events

A flexible event store allows fetching events from any time range. Traditionally, when using an event store to rehydrate an aggregate, all events are fetched to build up the state. Expressed as [first..last]

However, some aggregates may be more popular than others and outside its normal lifecycle. In such cases, these aggregates may have hundreds of events and rehydration takes substantially longer than normal and consumes far greater amounts of memory.

Through a process called snapshoting an aggregate’s complete state may be recorded as an event. From there, only a range starting from the last snapshot till the latest event is necessary. Expressed as [n..last]

Finally, in some cases a historical range needs to be examined. Expressed as [a..b].

There are two common cases:

- An audit or inspection question is posed, “When did x happen to aggregate y?”.

- A report must be composed. A range of events can be replayed, building report information.

Snapshoting is outside the scope of this series, however, as it comes with its own set of challenges. It’s imperative to be aware of the pattern if you are experiencing this problem.

The Ability to Push Events to Downstream Listeners

In the first article, one of the primary reasons for introducing event sourcing is to provide stronger guarantees when informing interested parties about data changes. Therefore, this requirement falls under the scope of responsibility of the event store.

An event store which does not provide this functionality may still be used but the burden falls on either the engineer utilizing the event store to provide a mechanism of informing interested parties or said parties must periodically query the event store looking for new events.

The Ability to Prevent Conflicting Changes Happening at the Same Time

Consider two requests entering a system at the same time, requesting to change a person’s name.

- Request One opens a transaction.

- Request Two opens a transaction.

- Request One changes the person’s name to “Alex”

- Request Two changes the person’s name to “Alexander”

- Request Two commits the transaction.

- Request One commits the transaction.

Despite starting last, request two beats request one to the punch. This software would leave users confused about why their name isn’t what they expected.

In a more series scenario, such as moving money between accounts, the risk can be much higher. A well-designed event store prevents such scenarios from transpiring.

The most accepted approach is a strategy known as Optimistic Locking. We’ll discuss this in detail in this article.

Design Overview

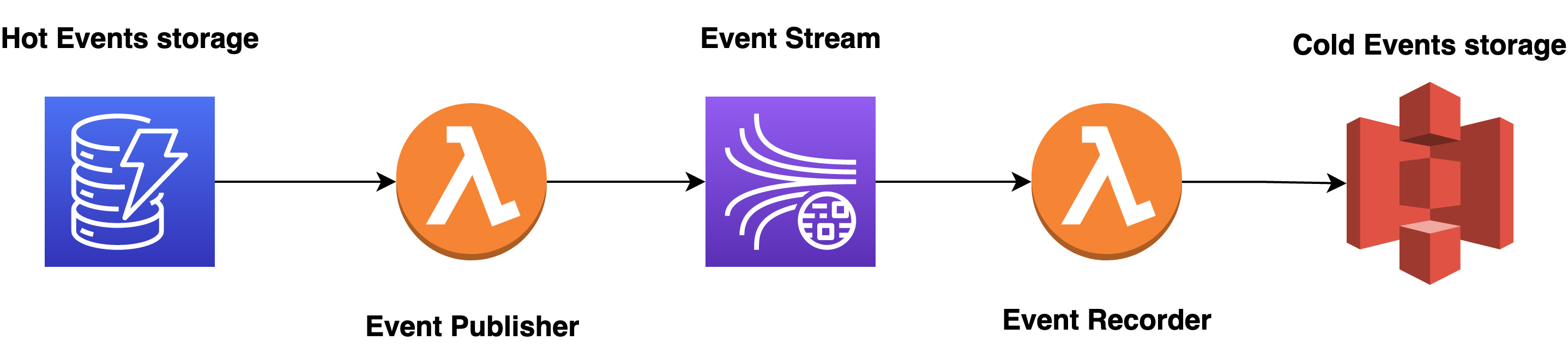

Our event store will utilize four AWS technologies to meet the key criteria:

- DynamoDB to store aggregate events and provide optimistic locking. It will act as hot storage.

- Kinesis Streams for pushing events to our to interested parties.

- S3 Bucket to store aggregates events for long term storage. It will act as cold storage.

- Two Lambdas:

- The first to capture newly added events added to our DynamoDB table and push them to our Kinesis Stream. This will act as an event publisher.

- The second subscribes to the Kinesis stream and records events to the cold storage (the S3 Bucket).

Hot vs Cold Storage

The hot event storage provides immediate access to events and allows the insertion of new events under optimistic locking. Here, guarantees are made about the data being inserted into the store. Any events added here gain immediate consistency.

Reading these events must be fast and in tune with our store’s non-functional Write requirements.

On the opposite side, cold event storage provides infrequent access more aligned with out store’s non-function Read requirements.

Large batches of events can be read without impacting write-side performance and subjecting ourselves to large overhead costs.

For example, with tools such as Athena, we can query our events using SQL to build reports or derive business insights.

DynamoDB Events Table

DynamoDB is a serverless Document DB from AWS that scales according to demand. A DynamoDB table does not belong to an overarching entity, unlike traditional databases.

To implement a table, it requires only a few things:

- A table name.

- A primary key, called a hash key. Must be unique.

- And optionally, a range key, which acts as a second lookup key. Must be unique only for its primary key.

The primary key will act as the lookup key for the value. It’s possible to provide additional lookup keys, called Global or Local Secondaries, but they won’t be necessary for our implementation.

Our first piece of Infrastructure as Code will be our table. We’ll define both the table and a event_store module for future components.

Defining the Module

Firstly, we’ll need to setup our infrastructure directory to use the AWS platform.

1provider "aws" {

2 version = "~> 4.57" # Version used at the time of writing

3 region = "us-east-1" # Change this if you wish

4}

Next, the event store. A Terraform module is simply a directory.

Our event store will require a name, which we can supply as a variable.

Next, we’ll define our events table.

1touch event_store/dynamodb.tf

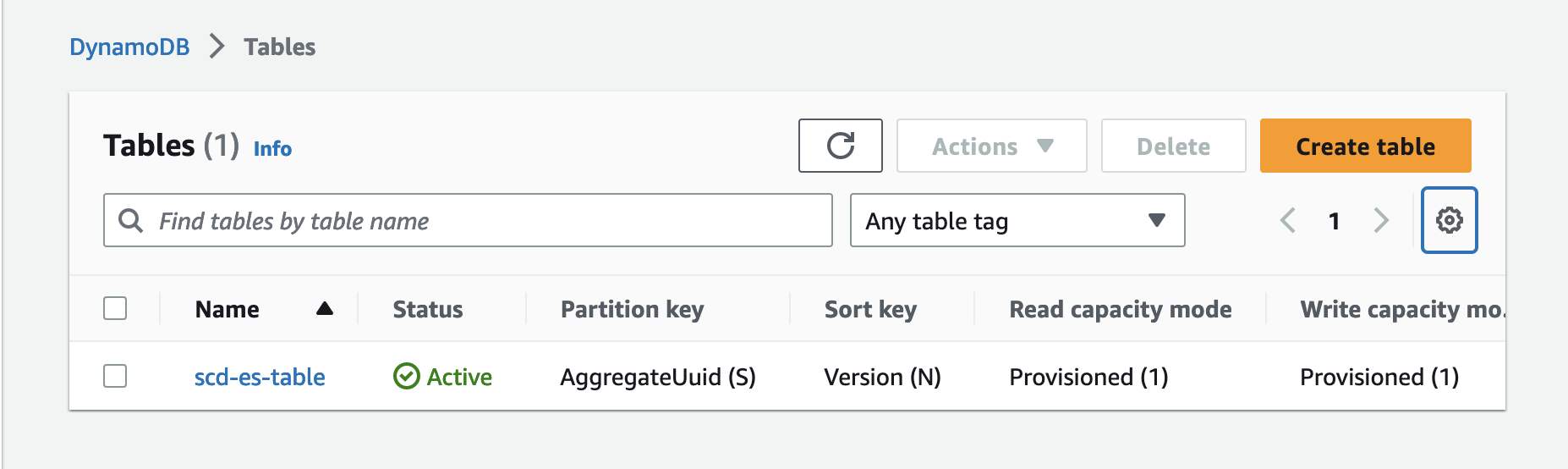

The hash key (primary key) will be named AggregateUuid and store our aggregate’s identifier.

We’ll also include a range key named Version. Versions facilitate Optimistic Locking, so we’ll dive deeper later. Unfortunately, due to a flaw in DynamoDB we must provide range keys upfront if we wish to use them.

1# event_store/dynamodb.tf

2

3resource "aws_dynamodb_table" "es_table" {

4 name = "${var.name}-es-table" # Note the variable here

5 hash_key = "AggregateUuid"

6 range_key = "Version"

7

8 attribute {

9 name = "AggregateUuid"

10 type = "S"

11 }

12

13 attribute {

14 name = "Version"

15 type = "N"

16 }

17

18 # For testing purposes, these values will do just fine

19 read_capacity = 1

20 write_capacity = 1

21}

Using the Module

Now our module is ready to be used. Let’s define the module in our infrastructure directory.

1touch event_store.tf

1# event_store.tf

2

3module "event-store" { # May be whatever name you choose. Must be unique.

4 source = "./event_store" # points to a directory

5

6 name = "scd"

7}

Our event-store module sources the previously defined custom module. By doing so, it will build all infrastructure resources defined within that module and treat them as a group.

We can build our infrastructure by running terraform apply.

1$ terraform apply

Logging into AWS and looking at DynamoDB, we can see our table. One really great feature of DynamoDB is that you can inspect tables and their items from the console which makes debugging a breeze.

We’ll implement additional components in future articles. For now, only DynamoDB is necessary for persisting aggregates.

Conclusion

We’ve reviewed our event store design and implemented the DynamoDB table component. The event store itself is broken up into different AWS serverless technologies used to meet the key criteria.

Next, we will start persisting our aggregates using the repository pattern and our DynamoDB table.